What was the genesis of the story?

Several different things came together over a period of time. I was working on a different novel, a failed novel really, and I’d promised myself I wouldn’t work on anything new until I finished that. So I had a year in which to think about the new project before putting pen to paper. This was shortly after 9/11 and also during the period in which I first really got into outdoor adventure. I was climbing at a gym several nights a week and outdoors every weekend. I was also going on a several mountaineering trips each year. It occurred to me that I wanted to somehow compare the dangers of being alone in the wilderness with those of the city, but I didn’t have a good vehicle by which to do so. A little later, I had a conversation with Abby Frucht about the use of the future tense in a narrative. I realized that might be a way inhabit both spaces at the same time. Later still, I read Jon Waterman’s account of kayaking the Inside Passage in National Geographic Adventure. I immediately knew that I’d found my wilderness. I asked myself who was taking that trip – I knew it wasn’t me, or even a character like me. I think around that time I was also influenced by Bridget Jones Diary. I really admired the effectiveness of the diary in that book, the way Bridget’s log of her cigarette and caloric intake becomes a metaphor for her search for identity. I wanted to do that but in a different genre.

Why did you choose to write from a woman’s point of view? Was that challenging to do as a man? Problematic even?

Writing from any character’s point of view is challenging. Constructing characters is challenging. Though we tend to think of gender as a defining characteristic in our culture, it feels less radical to me than the simple act of constructing a voice other than ones own. The only right any of us writers have to any of our characters voices is that we’ve constructed them. If they seem somehow representative of some group, then my belief is that we’ve somehow failed. That said, writing from a woman’s viewpoint helped me put distance between my own voice and views, and that of my protagonist. Ultimately, the person, or character, rowing from Prudhoe to Aklavik simply was Sarah, and Sarah wasn’t a stand in for women, generically, she was an individual entity, a unique construction. I once heard William Styron speak about The Confessions of Nat Turner. His feeling was that the narrative of a rebellious slave was available, untapped, that he was equally entitled, as a white man, to inhabit that voice as anyone else. That isn’t what I’m doing with Sarah. I’m not invested in speaking for women, or in providing a voice for issues that affect women in general. I’m only interested in a single character, Sarah, who happens to be female.

What research did you do for this novel? Have you ever kayaked in the Arctic or did you use a particular book?

I haven’t kayaked in the Arctic. I’m not even sure I’d want to. It sounds hard! I first got the idea to set a novel there from Jon Waterman’s account, Arctic Crossing. His book was extremely useful, as was Victoria Jason’s Kabloona in the Yellow Kayak and Jill Fredston’s Rowing to Lattitude. I also read a number of books about kayaking. Deep Water, Deep Trouble stands out in particular. I went sea kayaking a few times in Maine and New York. I surfed about every web photo and account of the Arctic that I could find. But all of that is about having the right technical data. Sarah’s relationship to adventure, exposure and nature are all very much based on firsthand experience. As I said earlier, while writing that book, I spent a great deal of time in the wild. Of course, my adventures were less exotic, really far tamer. Still, the experience of climbing at about the maximum of ones ability level, the rope strung out over the last piece of protection, the question of whether one has gone too far, pushed it too hard: I think that question of exposure is the same question on any adventure. The same goes for a long trip in the mountains. I remember when some friends and I went to climb Mt. Olympus on the Olympic Peninsula. It’s a climb that involves about every technical aspect of mountaineering but all at a moderate grade. We were, or at least I was, a real beginner though, and so we made mistakes like not taking enough food. We got lost in a fog. We second-guessed ourselves. I was genuinely scared and genuinely elated. Those experiences provided the other half of the research.

How did 9/11 influence your writing? What made you decide to incorporate it into the novel?

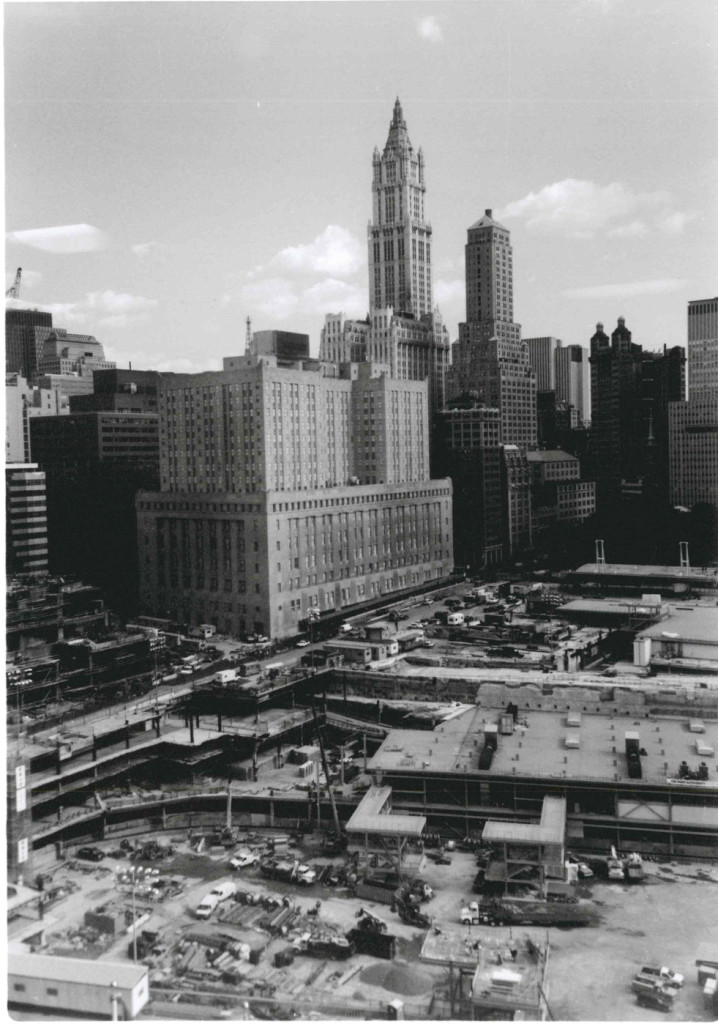

Well I worked in the World Trade Center. I was there on 9/11. I was in the stairwell on the twenty-eighth floor of Tower Two when it was struck. In that moment I felt more exposed than I ever have on any climb or outdoor adventure. I wanted to leave the experience, get off the climb, so to speak, and the only way to do that was to keep walking down the stairs, to finish it. It really affected my understanding of outdoor adventure pushed too far.

It was also this really present thing for a long time in my life. People I’d seen every day around my workplace were killed. The Borders Books I shopped at was destroyed. The Brooks Brothers where I shopped for work clothes was made into a morgue. A bunch of the firemen who died were from my neighborhood, and my local church seemed to hold daily full dress funerals. Beyond that – the day itself, the sort of atmosphere it created in New York – my place of work was demolished. I spent several months living in the Hartford Hilton during the workweek, and then a year or so working out of a temporary office, and another year – the last year I worked for OppenheimerFunds – with a view from my cube of the pit. So it felt like something I had to write about. I didn’t want to write about it too directly though. It’s too big an event. I don’t want to be the voice of 9/11 any more than I want to be the voice of women. It made sense to make Sarah’s father the WTC survivor, not her.

In a more general sense, I think that my brush with terrorism and its aftermath gave me a new way, a more concrete way, of thinking about the religious issues that I’d always gravitated towards in my writing. For all that the religious suicide bomber wreaks havoc on a swath of people, for all that that bomber plays a role in a broad political movement, he or she is ultimately engaged in a deeply personal, insular even, debate with God about his or her own faith. I always believe that fundamentalist terrorists are the ones least at peace with their God. After all, blowing yourself up along with a number of innocent people is an awfully big answer to the question: what would you do to prove your faith? I have to believe the question is equally loud. And that’s why when Sarah imagines Sara encountering a suicide bomber, she imagines that bomber as herself. She and the bomber grapple with the same questions. In other words, for me, writing about terrorism is a way of writing about religion and faith in a fashion that has very high, very concrete stakes.

What in your Jewish background made you want to delve into these particular themes?

I’m a lapsed Orthodox Jew, but I’m not entirely sure I know what that means. It’s something that I’ve tried to work out in my writing. On the one hand, I’m absolutely fascinated–in love even—with biblical exegesis, Talmud study, Hebrew translation. I strongly identify as Jewish. But I’m much less sure about things like God and faith and prayer. I think my generation struggles with a question of meaning. We’re not particularly religious; we don’t bother to have kids or families until we’re well into our thirties; we switch careers incessantly; until recently this last decade, we haven’t had wars or other great issues to grapple with. For me, that relationship to meaning, the struggle for spiritual awareness, is easiest examined by looking at religion, and the only religion I’m familiar with is Judaism.

Interesting enough, the main character has rebelled against her parents by embracing religion instead of rejecting it. Why did you choose this particular path for your character?

I had her become religious for several reasons. I’ll start where my last answer left off. I think that my parents’ generation, or maybe my grandparents’ generation, rebelled against religion. My generation, however, was largely raised without either the religion or the rebellion against it. That creates a void – one that as a formerly religious person, I was really unaware of until my early twenties. I wanted to explore what it might be like to fill that desire for meaning with fundamentalist faith. And It think that’s a trend we can see all around. Fundamentalism is on the rise and its proponents’ parents were not necessarily devout.

The second reason, and my first reason alludes to this, is that it wasn’t the path that I took. I did leave orthodoxy, and that was part of my own rebellion against my upbringing. Again, I wanted to see what the other end looked like.

Finally, I’ve been really fascinated by the way God is depicted in Job and in The Psalms. He’s a really difficult figure. I began to wonder what it meant to depend upon the comfort of divine plan in order to make the world livable, if that necessity implied a God who’d made a world not really worth living in. I developed a series of positions a character might have in relationship to that paradox. The first was of the character who rebels so strongly against God that he needs Him to exist in order to have something to rebel against. The next was the character who finds faith, and who then blames faith for events in the world. That’s of course Sarah, who believes, but worries that believing got her parents killed. And finally, there’s the character who desperately wants faith but can’t quite access it. This one’s something like a Puritan who hasn’t been selected for Grace. I think Sarah’s father is a prototype of this character. In my next novel, I flesh this idea out further.

I guess I also wanted to discover a more sympathetic personal view towards faith and towards believers. Developing Sarah’s character helped me do that.

So what are you working on now?

I’m just putting the finishing touches on a novel that explores a character who desperately wants to believe in God but can’t. He’s an American-raised Israeli who prevents a suicide bombing in Tel Aviv by shooting a woman about to blow up a beachside café. However, he can’t resign himself to the idea that he’s killed another human, a woman, even though it was obviously necessary. He loses his faith and comes back to the US. Eventually, he begins to contemplate what it might mean for him to carry out an attack in New York as a way of reconciling his own faith.